Posted on

Research has shown that a child’s spiritual foundation and view of the world is developed within their first six years of life (Gillian, 2007). When children hear consistent messages about Christianity at home, at church, and at school, it solidifies their understanding of God and they can practice His teachings in a variety of settings. Early childhood educators help to share these messages and model behaviors for young children in their care.

Master of Education instructor and early childhood consulant, Dr. Jennifer Sturgeon shares applicable lessons or ideas for early childhood teachers working in Christian schools and in a public school setting.

While engaging in class discussions at Northwestern College, graduate students who work as early childhood educators shared their experiences of working in Christian schools. Stories shared included kindergartners pointing out God’s creations while on a nature walk, preschoolers praying for a classmate who was at a grandparent’s funeral and creating artwork representing Heaven, and first graders playing a Bible detective game to better understand the Word of God.

When reflecting on their experiences in the classrooms, these early childhood educators pointed out a strong positive impact of faith-based education on academics and behaviors. I decided to investigate this further and had the opportunity to gather input from focus groups of educators from grades Pre-Kindergarten to Grade 2 on the positive impact that faith-based education has on both individual students and the overall culture of their environment.

Developing Faith-Based Routines

When we think about our youngest learners, students in preschool or in the primary grades, they often do things out of routine and habit. There are certain habits that we have as Christians to help build and strengthen our faith. Praying is modeled for children and becomes a habit early on. Our youngest learners may not fully understand or comprehend the significance of Christian values, however, we do not need to wait until they fully understand (Brim, 2016). The teachers that participated in the focus groups mentioned that they are setting the stage for the child’s future and helping them to develop those faith-based habits to prepare them for when they reach an age where they can begin to reflect on and understand the different aspects of faith.

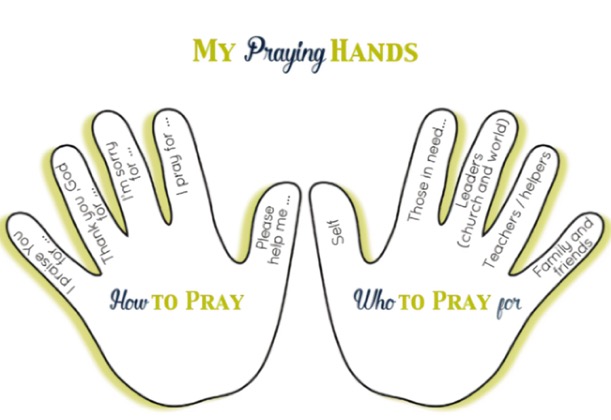

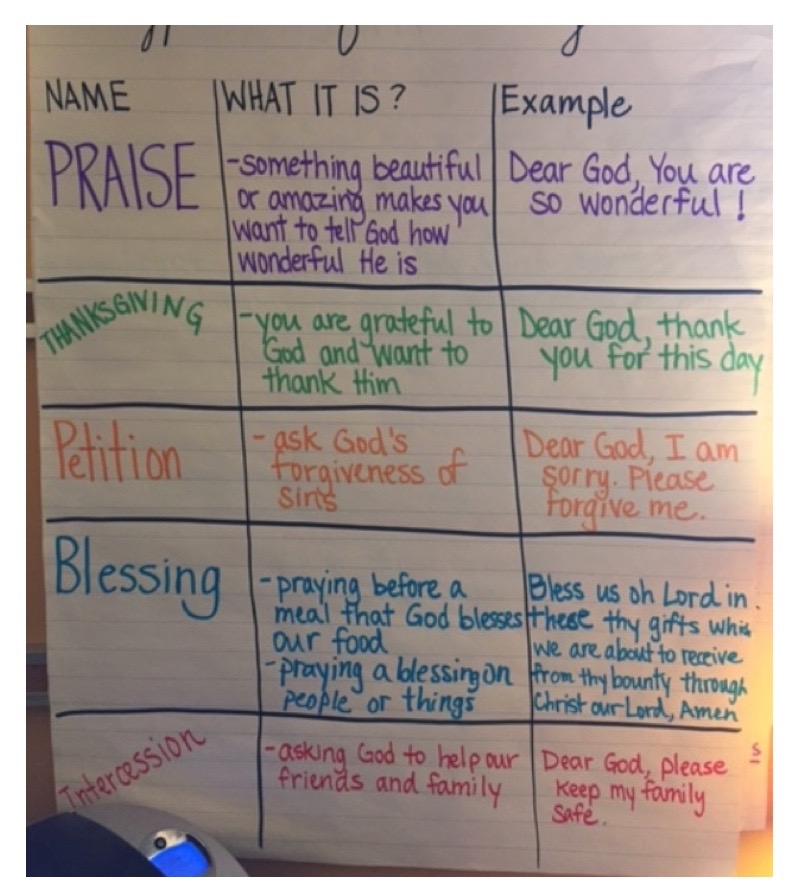

Teachers include prayer as part of the school day and teach children that through prayer, we can communicate with God. Children are encouraged to offer a silent prayer to God each day and are taught the importance of sharing a prayer with peers in their classrooms. When our youngest learners pray, it strengthens their faith and unity and helps them know that they are one before The Lord (Covey, 2018). Prayer is also used to help children take a deep breath, calm down, handle social situations, and complete challenging academic tasks.

The children also take on different roles and responsibilities related to prayer to help take ownership of their faith. For example, classroom jobs assigned to students include setting up the daily prayer space, writing out the petitions, and choosing the Biblical story or song.

Academics

According to the Council for American Private Education, students who attend religious schools score at an academic level about 12 months ahead of their counterparts (2020). This begins with the strategies used and the curriculum implemented at an early age. After listening to the teachers in the focus groups discuss academics, it became clear that in faith-based programs or schools, academic achievement was a priority at a young age. There were consistent findings that the focus was on preparing children for the next grade level and beyond.

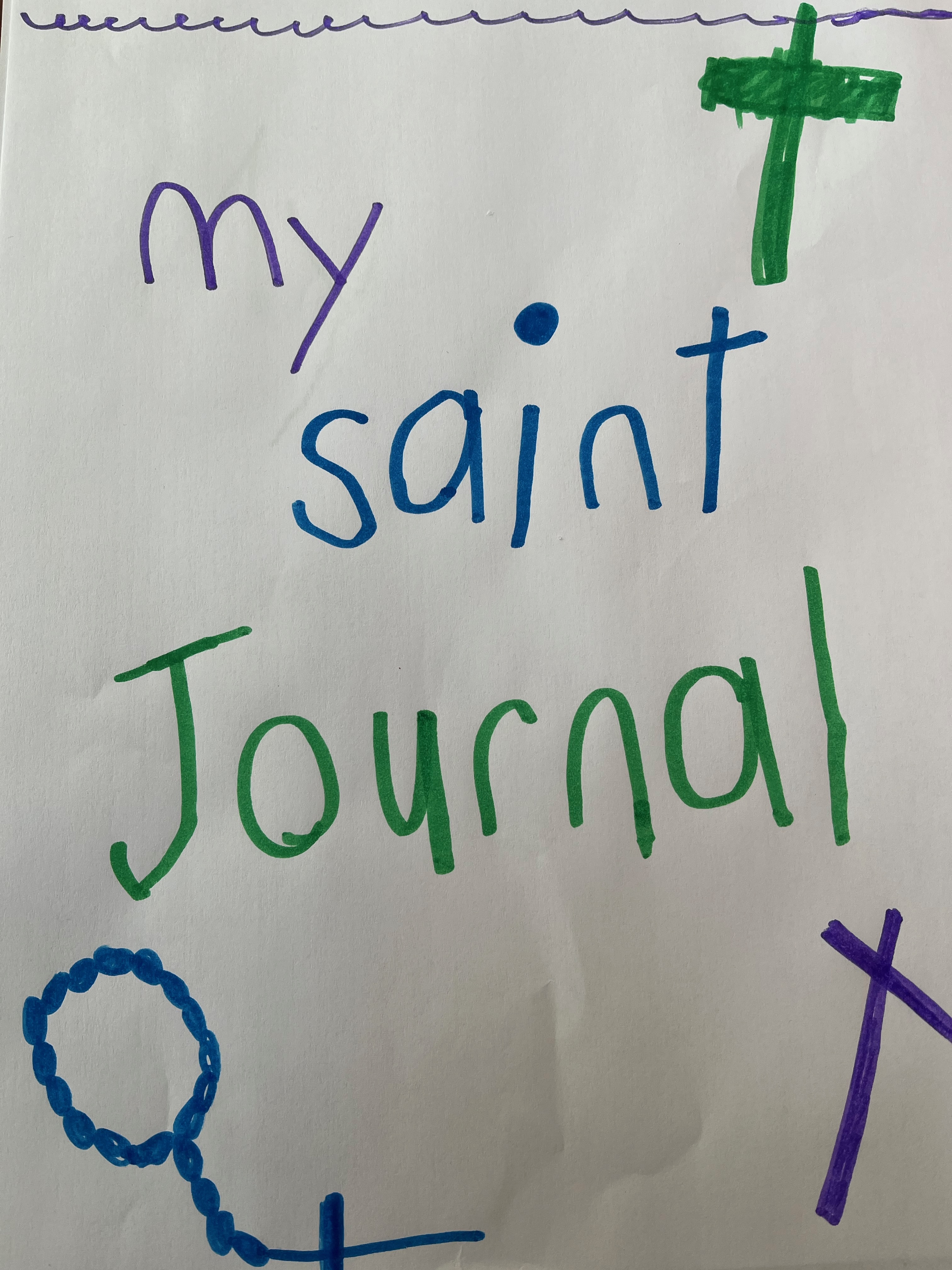

The educators stressed that religion and faith-based practices can be effectively embedded using an interdisciplinary approach. There are countless ways to include faith in all areas of the curriculum. Several examples related to literacy were shared. One teacher described an activity that they did related to descriptive writing. Each student created a Saint Journal and wrote about the characteristics of the saints and then shared their writing with their classmates. Another example focused on teaching the literary elements, such as plot, characters, story sequence, and conflict, and how teachers can use stories from the Bible and have the students draw or write in response the story and the lessons taught.

In addition, the teachers spoke at great lengths about how the students’ talents and gifts from God are promoted, as well as individualization of learning styles. Those teachers who work in early childhood settings have a wide range of children enter their classrooms, with a variety of needs, skills, and background experiences. They focus on the unique potential of their students and modify the curriculum to meet the needs of all students and support each student to reach their potential. They felt that in faith-based settings, the educators were truly there for the students and were willing to go above and beyond. This led to more of a collaborative spirit and everyone coming together to help the students that needed extra assistance.

The focus group participants also noted that the students in faith-based classrooms appeared to be more comfortable taking risks and speaking up in the large group because a culture of kindness and love that had been created in their classrooms. They noted that students were more willing to raise their hand to ask and answer questions without embarrassment or fear. When working with a partner or in a small group setting, peers were helpful and assisted their classmates without judgment. They noted that these peer interactions gave students more confidence.

Positive Social-Emotional Skills

The teachers shared common themes that connected faith-based learning to positive social-emotional skills, a culture of kindness and collaboration, and a safe learning environment. Christian morals set children up for a lifetime of success. Between the ages of two and five, children begin to display morally-based behaviors and beliefs (McKay, 2014). When children are in settings where they are taught these morals, their social-emotional skills and their daily behaviors are impacted. The teachers who explicitly taught Christian values and spoke openly about faith daily in the classroom saw an increase in positive social-emotional behaviors when they compared their experiences in faith-based classrooms to other teaching environments.

In faith-based classrooms, early childhood educators serve as role models in faith by teaching the values of Christianity, establishing trusting relationships where children can reflect on actions and learn from mistakes, and encouraging kindness and friendship (Holloway, 2006). The teachers noted that most of the children in their faith-based classrooms excelled at turn-taking, sharing, and using of kind manners. They shared that children as young as three-years-old could manage their emotions and problem solve when frustrated or upset. They attributed this to both teaching those Christian morals as well as children feeling they are cared for and safe in their classrooms. Children are instructed to calm down, take deep breaths, and pray. They are respected as valuable members of the classroom and are taught how to handle their emotions in a constructive way. The teachers in the classroom model appropriate behaviors and guide them through the process.

Culture of Kindness and Gratitude

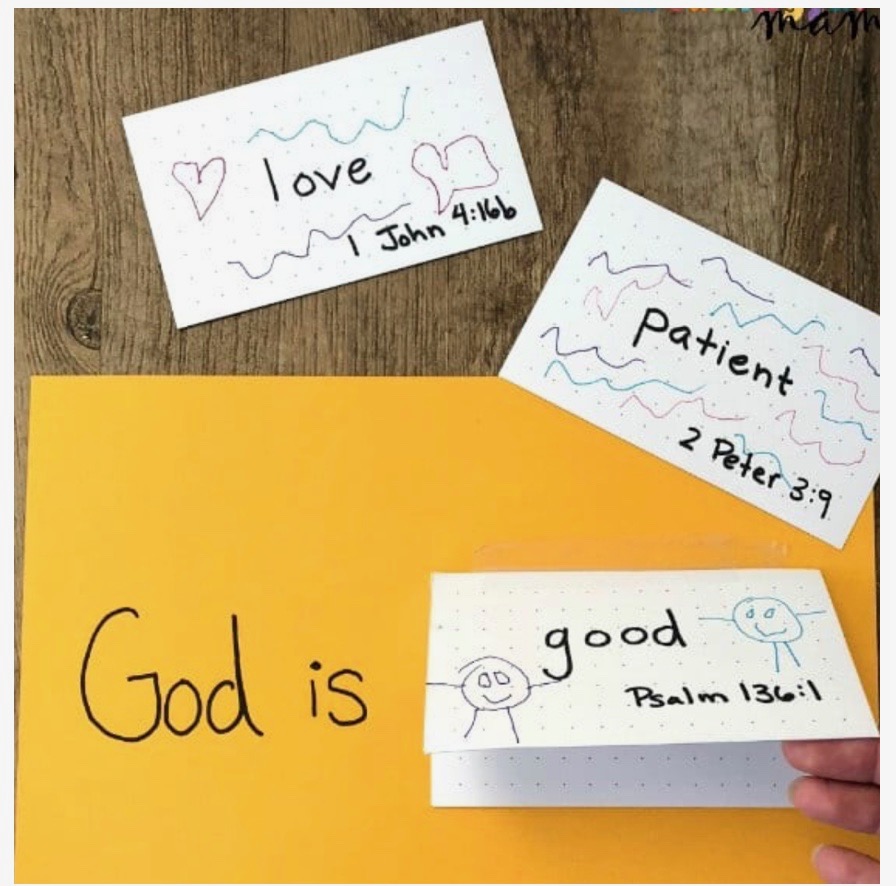

Learning about God and listening to Bible stories at an early age helps children to develop empathy (Oswalt, 2021). This increases their understanding of other’s perspectives and leads to more productive and positive communication. The graduate students mentioned that children are taught forgiveness at a young age. We all sin, and everyone makes mistakes, but we must forgive one another.

In faith-based classrooms, children are taught to live like Jesus. At a young age, students are taught about gratitude and focus on being thankful for what they have. Through a variety of projects, they provide service to others. A common theme shared was service-based learning projects, in which the children collected donations for others, created art for others, or did a variety of good deeds around the school.

Safe learning environment

Faith-based early childhood classrooms provide our youngest learners with a safe emotional and spiritual environment. Children are taught to be respectful and to love one another and conflicts are discouraged. The children are taught that bullying is not kind and practice different ways to solve problems as they arise. The teachers in the focus groups mentioned that students are consistently allowed to be themselves and to express their ideas freely without being judged by their schoolmates or teachers.

Specifically mentioned were the children who had experienced high levels of stress and trauma in their lives. Teachers shared that part of creating a safe environment included teaching children to trust in God, which led to less anxiety in the classroom setting. Young children experience big emotions. One shared a story where the child who had experienced several challenges came to school crying and the difference it made when during their opening routine when the teacher asked for petitions, someone prayed that she had a better day.

Although the majority of the focus group participants were employed in faith-based settings at the time of the discussions, the consensus of the group was that these values can still be instilled in our youngest learners in a public-school setting. When teachers cannot lead the class in prayer or directly speak about Jesus and His teachings, they still find ways to model kindness, compassion, and other key values from the Bible.

About the Author

Dr. Jennifer Sturgeon is a Master of Education Instructor in Northwestern's online M.Ed. program and consults with administrators and teachers across the country who are using curriculum and assessment materials produced by Teaching Strategies, LLC, and trains staff on the best practices for early childhood education.

Posted on

This blog post was originally published on the Region 13 Education Service Center website.

Educators know the difficulties of the summer slide—the phenomenon where students lose significant gains in math and reading over the summer months. But now, research is coming out on the devastating effects of the so-called COVID-19 slide. We must pay attention to the informal and formal student data surrounding the implications and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and what we can do to address it.

According to a research brief from NWEA (2020), “Policymakers and educational leaders have the unenviable responsibility of making difficult decisions well into the 2020-2021 school year and beyond. Now more than ever, we need school data to inform evidence-based policies to support our students, teachers, and families on the path to recovery” (p.2).

As leaders, we must take this current information and begin to plan with our teams and stakeholders, at whatever level, to map out how we are going to address the areas of significant gaps in learning that students are currently enduring.

In a recent presentation from the Department of Education called, Learning in a Pandemic, I heard some fascinating statistics on the state of education in the US. Let’s dive into the school data and discuss some takeaways. But remember that with any data analyses and interpretation, there are always multiple variables and extenuating circumstances. So we must use caution when making practical, short and long-term decisions.

COVID-19 Impact Data

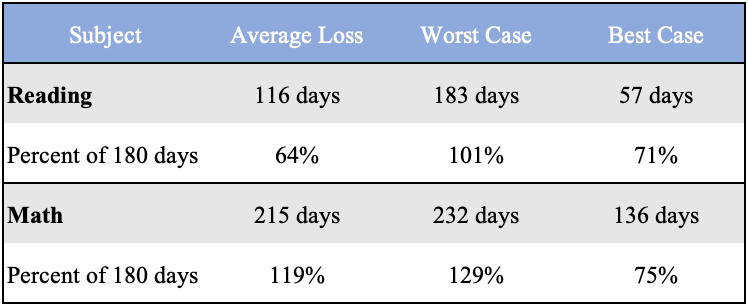

In the COVID-Sim project research study, Dr. Macke Raymond, the Director of CREDO, compared fall 2019 student data with fall 2020 student data from the 20 states in this simulation project. It estimated what students would have learned had COVID-19 not occurred and the COVID-19 impact on learning, with help from the NWEA.

Math Losses vs. Reading Losses

They found that learning losses in math were greater than reading in every state. They hypothesized that this is due to the fact that we use reading (language arts) in our day-to-day lives more frequently.

Equity Effects

When comparing the loss estimates between high-minority/high-poverty schools and low-minority/low-poverty schools, they found that the first group has the largest amount of learning loss and the second group has the smallest.

Dr. Macke Raymond stated that “students who were already at the back of the pack, are the ones who had the largest impact, and are being moved even further back relative to the impacts for other students.”

So COVID-19 magnifies pre-existing achievement gaps. The effects are inversely related to overall achievement: students with lower achievement have greater losses. This means that we can no longer assume common starting points and fixed pace of learning.

Learning Loss Based on School Attendance

This graph represents students from the 20 states examined in the study attending the traditional 180 days of school and their learning loss or not attending the school over that school year. For example, the average loss of learning was 64%, or in other words, as if they had not attended school for 116 days of reading instruction. With math, the worst-case scenario was 232 days of loss of learning for some students (as if they did not attend school for 232 days at this time).

Recommendations Based on Student Data

It’s hard not to feel discouraged by the student learning loss and the widening achievement gap. But knowing what we’re up against can help us as we plan for the future. The presentation by Dr. Ailiyah Samuel, Senior Fellow of Government Affairs and Partnerships, offers some suggestions.

Academic remedies will likely take years, but this is only part of the equation. We will also need new approaches to schooling and the new or different use of teachers. For example, having a concentrated, expert teacher of master content can ensure students are meeting the learning objectives. There could also be a wider range of school setting options such as virtual, blended, one room with multi-ages, etc.

Furthermore, the need for assessment has never been greater, as even the best students will have up to a 50% loss in learning. A lack of data on students in underserved communities also makes assessment a key component in getting back on track.

Planning for the Future

When making plans to combat the COVID-19 slide, be sure to have at least a three-year lens on everything from technology to finances. A study in Argentina during the 1980s teacher strikes found that the negative effects of students missing school followed them into adulthood and had a disproportionate effect on low-income students. This information can also help us make sure we are allocating resources equitably so that all students can recover from the learning loss.

In addition, examine current teacher certification and reciprocity across districts and states (i.e. we could access “expert teachers” from one state for another state and not be held back by “regulations”). Additionally, place an increased focus on math (as it is cumulative) and brainstorm how to make it a day-to-day activity like reading.

Personally, you can watch the complete webinar from the Department of Education and review the concrete steps of 5 ways to lead and adapt through a crisis (from the Center for Creative Leadership). Don’t forget to ground your work in Radical Empathy. “Radical empathy is a concept that does exactly that – it encourages people to actively consider another person’s point of view in order to connect more deeply with them.” ~Jacqui Paterson

And finally, just begin. There is no perfect answer to teaching in wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, but looking at student data and taking action is crucial for our students’ success.

Tell us what you think!

Tweet to @NWConline

About the Author

Dr. Wendy Kerr is a Master of Education Instructor in Northeastern's online M.Ed. program and works as an Administrative Specialist for Educator Evaluation and Leadership at ESC Region 13 in Austin Texas.

Posted on

Recently I heard a sermon about rejoicing with those who rejoice and weeping with those who weep (Romans 12:15). My fear of missing out (FOMO) spikes when I see social media posts of my vacationing friends and this was a good sermon for me to ponder. It is a lesson I have tried to teach my own kids in my own house. Among my six kids, there hasn’t always joy when one kid gets to choose the breakfast cereal or sadness when one kid gets hurt on the new skateboard.

I enjoy visiting with new teachers and recently I had a conversation about classroom management with a new elementary teacher. He has a large and busy class. He was telling me that behavior management has been the biggest challenge for him. The behavior exhibited by one child is particularly concerning. This child often thinks he gets the short end of the stick or another child is the teacher’s favorite. He complains that others get better seats, more time, a better deal in general. He disrupts the class often.

The teacher told me about the interventions he was trying. He had given the child frequent breaks; preferential seating, including a standing desk; fidgets; a handheld gaming device to take on the bus. I thought that his plan sounded good. At the end of the conversation though, the young teacher asked, “What will the other kids think of him being rewarded for his behavior? Won’t they want to act like that too?”

The question stopped me up short. Did the accommodations seem like a reward? Would the other kids in the class begin to act out so they too could have their behavior “rewarded”?

What do you all think? I know behavior can be contagious, but I do not think that kids without behavior issues will start misbehaving to see if they too can have accommodations. Will all of the kids want fidgets? Perhaps. Will all the kids need fidgets? Probably not. Teaching positive behaviors is difficult for all of us, especially for new teachers.

I taught my own kids a little song when they were little. I sang, “When good things happen to people we love we are…and then I would point to them and they would say GLAD!” We would continue by saying, “When bad things happen to people we love, we are SAD!” My goal was to teach them to rejoice with those who rejoice and weep with those who weep. I hope that teachers can do that too. Can we create communities where we all want the best for all kids in the class?

Tell us what you think!

Tweet to @NWCOnline

Teaching positive behaviors is difficult for all of us, especially for new teachers.

— NWC Grad & Online (@NWCOnline) February 15, 2021

How do we create communities where we all want what's best for all in the class; what do you think? @heits1 https://t.co/pUgmMURcGC

About the Author

Dr. Heitritter currently serves as a special education strategist with the Northwest AEA. Prior to her retirement from Northwestern, she served in many full-time roles including department chair, licensure official, and professor of undergraduate and graduate education courses. Before joining Northwestern's education department, Dr. Heitritter served as a language arts consultant and taught at both public and Christian elementary schools.

Posted on

Parker Palmer, American author and educator wrote in his book The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life, “I am a teacher at heart, and there are moments in the classroom when I can hardly hold the joy. When my students and I discover uncharted territory to explore, when the pathway out of a thicket opens up before us, when our experience is illumined by the lightning-life of the mind-then teaching is the finest work I know.”

This is my first year back in K-12 education after many years as a teacher educator at Northwestern College. I am working as a learning strategist and the schools I serve have been open for in person learning since August. The educators I work with are universally grateful to be back learning in person with kids. In fact, Covid has made it so teachers get almost more time with their students than before the pandemic. Kids come directly to their classrooms when they arrive at school. They stay in their own classrooms all day. Specials are delivered in the classroom so as to reduce exposure. Teachers spend any breaks they find sanitizing. They take their own students out for recess to limit contact with other classes. They contract trace after exposure. They arrange their room and change their instructional practices to keep kids as far apart as possible. The pandemic has certainly presented teachers and students “uncharted territory to explore”. Sometimes these challenges have been joyful, but for many educators, the pandemic-induced uncharted territory has been stressful.

Still, through the stress, the courage and strength that I see every day from the teachers and students I work with has been incredible.

Teachers have faced the extra and challenge with the knowledge that learning in person depends on their work. Teachers have taught kids virtually and in-person simultaneously. They learned new technology and deployed it as they learned it. They have fostered incredible community within their own classrooms. They are surviving a pandemic with their students and together they are building memories that will last a lifetime.

In the same chapter, Palmer goes on to say, “Teaching, like any truly human activity, emerges from one’s inwardness, for better or worse. As I teach, I project the condition of my soul onto my students, my subject, and our way of being together.” Well, Mr. Palmer, if it is true that teaching holds a mirror to the soul, I can answer that the soul of the teachers I see is just fine. In fact, the condition of the soul is so fine, it is joyful to see.

Palmer, P. J. (2017). Courage To Teach: exploring the inner landscape of a teacher's life - 20th anniversary edition. JOSSEY-BASS.

About the Author

Dr. Heitritter currently serves as a special education strategist with the Northwest AEA. Prior to her retirement from Northwestern, she served in many full-time roles including department chair, licensure official, and professor of undergraduate and graduate education courses. Before joining Northwestern's education department, Dr. Heitritter served as a language arts consultant and taught at both public and Christian elementary schools.

Posted on

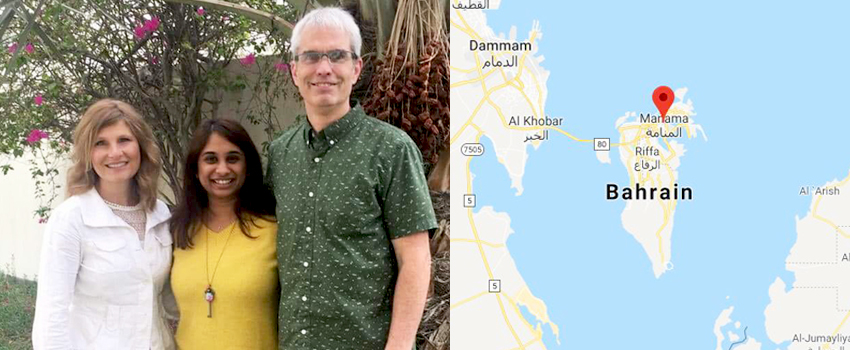

When our dear alum, Christine Roy, asked us to do some consulting on learning inclusion and peer learning communities at Al Raja School in Manama, Bahrain, we took her up on a globe-trotting adventure – in return, I felt impacted more than I consulted.

When our dear alum, Christine Roy, asked us to do some consulting on learning inclusion and peer learning communities at Al Raja School in Manama, Bahrain, I’d like to say I jumped at the opportunity. How many times do you get a chance to speak into the development of new programs that significantly impact teaching and learning in another country? How many times do you get to partner with a former student on work that is truly valuable? I should have been elated. I should have.

The truth is, I was a little afraid to accept Christine’s invitation. I was afraid of traveling to the Middle East; Bahrain is on the Persian Gulf, surrounded by Saudi Arabia and near Yemen, Iran and Iraq. I was afraid of the culture, particularly how I would be treated as a western woman. I was afraid of the language barrier. I was afraid I wouldn’t understand the context of the school, and end up offending the teachers. As my colleague Derek Brower can attest, I was even afraid of the food. BUT I was more afraid of being someone who missed out on an opportunity because of fear, so I said yes.

Do you know what we found during our week in Bahrain?

Multilingual, multinational children who laugh, learn, sing, dance and play together without any perceptible discrimination. Parents wearing everything from hijabs to skinny jeans, keffiyehs to Oakleys, who openly love their children. Teachers from countries like Bahrain, Egypt, Sri Lanka, India, Canada, the US, Great Britain, and Indonesia working together in harmony and purpose—on fire for interdisciplinary collaboration and student success. A school right next to a mosque and a Christian church. Christians and Muslims and Hindus who are friends and coworkers.

Tolerance. Generosity. Kindness. Hospitality.

Kharak tea, tandoori masala, qouzi, khuboos, shawarmas and the best murgh makhani I’ll ever eat in my life. And of course, our Christine Roy, a young teacher leader who is leaning in to the work God has laid upon her heart.

We went to Bahrain to help Al Raja School, but I suspect we left with far more than we contributed: a renewed appreciation for the beautiful diversity of God’s kingdom, and the knowledge that we are as similar as we are different. I can’t wait to go back.

Posted on

“Research shows that providing children with a schedule of events will produce one of the greatest returns for a smoothly run classroom"

Structured blocks with visuals

In my second grade general education classroom, I have a wide variety of abilities and skillsets. I have 23 students and one-third of the students have an IEP for academics and/or speech, or are English Language Learners. Because of the diverse population in my classroom, I knew that I would need to have very structured routines throughout the day and have a daily visual schedule as well as visual schedules for expectations during each subject area. A structured reading block has greatly benefitted my students, especially those with learning disabilities. It provides the structure with visuals to help them transition quickly to each reading station.

New challenge

At the beginning of October, a new student moved in from out of state (I will call her Jan), and our administrators felt as though I would be a good fit for her knowing that I have a background in Special Education. After first meeting Jen, it was evident that she had a very difficult time verbally communicating. I conducted some brief formative assessments and was able to conclude that I would need to differentiate everything in my classroom to meet her needs, including the structures I currently had in place.

After observing Jan and collaborating with administrators and colleagues, we decided that in whole-group activities, she is able to follow her peers and transition with the rest of the class, although she may not participate, but small group transitions were a concern. Hoping that I could take some time to teach her the expectations for transitioning independently by finding her name on the board and going to the station she is assigned to, I spent a couple of weeks walking with Jen to the screen each rotation and finding her name, then walking with her to her station. Slowly removing my support each day and phasing out my help, I learned that she is still not able to find her name on the screen on her own. Spending this extra time supporting her was taking me away from my small group instruction, so I met with my principal to ask what supports I needed to put into place so that I was not taking away time from my other students. We came up with a plan that I could create a more basic visual schedule for her.

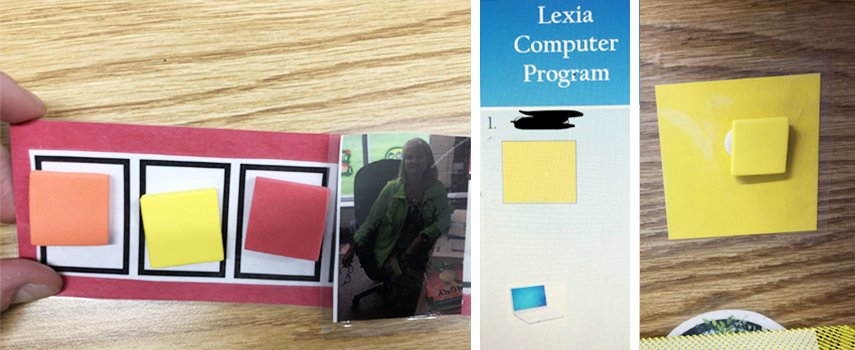

First try: color-coding

At first, I color coded each station and would verbally tell her what color station she needed to go to, as well as color-coding her name on the screen so she could find what color her name is and go to that color station. For example, the teacher table is orange, so I would have her name and teacher table printed in orange on the screen and verbally prompt her to go to the orange station.

On the first try of this approach, I learned that she is not able to identify colors, so it was back to researching other methods. I was determined to find a system that would work for Jen, but would not be too much of a distraction to my other second graders. While researching, I was able to find a book called “Everyday Education: Visual Support for Children with Autism”. I learned that “The purpose of a clear physical structure is to limit the chaos for the child as much as possible and to make it easier for the child to understand what is going to happen next”. I need to rearrange the physical set up of my classroom!

Overcoming barriers

With this in mind, I restructured my classroom a little bit, so it would make more sense for Jen and work for the whole class. I began with creating a segregated computer area, and another iPad area (rather than the students taking the devices to their desks). This makes it easier to understand that when she is at her desk, she is working on deskwork and not on a technology task. Some areas of my room were already labeled with colored squares from my prior attempt at helping her with transitions, so I added squares to the areas that were not already labeled. I also created a work station three-drawer cart for her independent tasks that are color-coded with squares of paper, so she knows what her task is during independent work.

She will now have a visual schedule strip with colored foam squares on it. Each time she is expected to transition to a small group or work station, she will find which color square is next on her schedule strip and match it to the colored square at the station she is going to. Each station square and foam square have a piece of Velcro so she will Velcro her foam square to her destination square. This project has taken a lot of time and research, but I know it will be beneficial to this student and will allow me to focus on teaching my small groups rather than helping her transition to her stations.

Worth it

It’s worth the work, the trial and error, to create the best learning experience for all students. You may be only one more test away from overcoming a learning barrier for your most challenging student. Observe, communicate with the student and collaborate with others to find the solution that helps. Be encouraged, colleagues!

About the Author

Morgen Bennet teaches 2nd Grade at Leeds Elementary in Sioux City, IA, and is currently an M.Ed. student in the Educational Administration + Principal program. Teaching came naturally to her as a career choice. Coming from a family of teachers, she also loved school because of the great teachers and staff and now hopes to help her students enjoy school as much as she did.

"In each of my teaching positions so far, I would definitely say that my favorite thing about teaching is how rewarding it feels to see students feel successful! I LOVE seeing their smiling faces when they are able to master a concept. I can't help but smile when parents tell me that their child enjoys school and is gaining confidence."