9 Practices to Make a Compelling Difference in K-12 Systems

Download the Notable Practices white paper

By Megan Alexander, Instructional Coach and Prinicpal Endorsement Program student

I have been listening. Observing. Taking notes. Noticing patterns.

For the last three years, I have served as a school leadership coach, trained via NYC Leadership Academy protocols. It has been my privilege to come alongside fifteen principals in ten different buildings on behalf of the Administrative Support Program through School Administrators of Iowa. In these schools, I have been listening, observing, taking notes, noticing patterns.

Concurrently, as an instructor of the “Teacher as Leader” graduate course and director of the Master of Education program at Northwestern College, I have engaged in discourse with teachers and principals from all of the country, hearing about what practices support and what practices thwart effectiveness in K-12 educational systems.

Here in Iowa, this kind of constructive discourse has ramped up since the Iowa Legislature passed the Teacher Leadership Compensation Program, now in its fifth year of operation. Its primary focus was to provide a system of distributive leadership that empowered teacher leaders to provide instructional leadership to peers in their respective buildings. The subsequent conversations about instruction and learning have been some of the most robust experiences that I have observed over a 37-year career as a teacher, principal and superintendent.

Visiting schools during this time of shared leadership between administrators and instructional coaches, I have witnessed different attitudes toward change. We educators realize that change must happen: to stay the same is to fall behind. I have observed school cultures that promote transformative teaching and learning, and other school environments that erect barriers that impede systemic change.

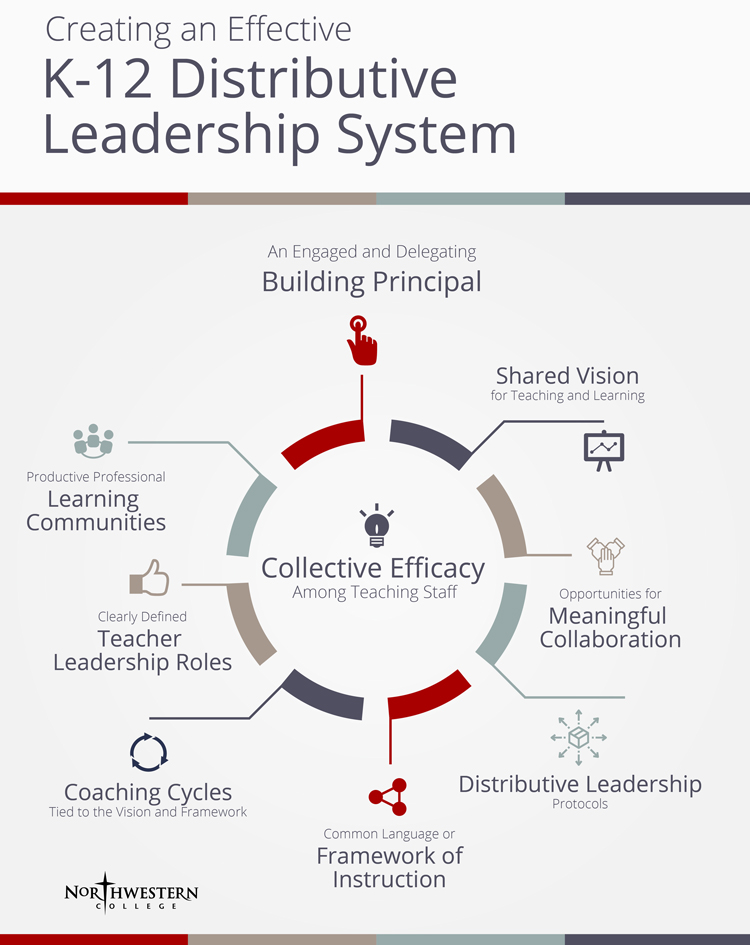

Over time, I have noticed nine notable practices that make a compelling difference in creating an effective K-12 distributive leadership system.

Click on each practice for an expanded explanation provided by Instructional Coach Megan Alexander, Boyden-Hull Community Schools, and currently a student in the Principal Endorsement program.

All staff should have the opportunity to be involved and be heard so that there can be collective agreement on a shared vision.

Having a shared vision and teaching for learning is at the forefront of important principles that should guide a school and all of its operations. What do we, as a collective group, want teaching and learning to look like? The following eight notable practices as described in this blog cannot be set in place within a school without first establishing the vision for what the school community believes to be the overall vision for what the culture and efforts within the organization should be.

The most crucial element of a shared vision for teaching and learning is the buy-in that all staff and administration have in regard to the vision. Administration and leadership must buy-in, because they will be the driving force in developing the school culture that cultivates efforts in working toward the shared vision of the school. However, possibly even more critical is the buy-in of the teachers. Teachers are the ones making the day-in, day-out decisions about students. If a shared vision has been established and collectively agreed upon, the leadership within a school can trust that teachers are consistently making decisions that align with that ideal without having to micromanage.

Leadership should deliberately seek input from all staff affected by decisions or potential change.

People feel valued and respected when they believe their leaders desire to hear their ideas and input and understand their points of view. Too often, decisions are made in a school by the administrators and school leaders who think they know what teachers think, feel and need, but actually may not have a clear understanding of what’s truly happening within the walls of each classroom. As a whole, good leadership has been shown to improve teacher motivation as well as positivity in the work setting (Five Key Principles, n.d.), so what does “good leadership” really look like? Research would argue that one huge emphasis in establishing a positive school climate in which teachers collectively work toward student achievement is the need for opportunities for meaningful collaboration. Providing teachers the opportunities to work together purposefully and communicating that their collaborative work is powerful and necessary in moving toward the shared vision for teaching and learning increases professional engagement and creates an overall more positive work environment and successful school system.

Professional principles should consistently guide how team members treat each other.

Moving toward the vision Needs to be consistent growth—how? By setting up systems and systems by which the school, learning, and activity within the school is being consistently evaluated and improved. This task is much too great for one person or even one team to take on, and the insights and expertise each staff member are too valuable to dismiss. The collective efforts of the entire staff through distribute leadership are necessary, and teachers must play an active role in helping move toward the school’s vision for teaching and learning. Districts and buildings must ensure that a systematic approach to involving and engaging all staff members and the work to be done and the initiatives to be taken. Some examples of effective norms (Carter, 2018), as further discussed in the eighth notable practice, “Productive Professional Learning Communities,” but that also may be appropriate for committee work include:

- We will have an agenda purpose for each meeting.

- We will avoid side conversations, they are distracting and disrespectful to the speaker.

- We will limit discussions that will monopolize time.

- We will start and end on time (time keeper).

- We will treat members with honesty and trust.

- Our goal is to help each other.

- We will practice confidentiality.

Whether a district uses APL, NIET, Marzano’s or Danielson’s framework, common vocabulary and assessment expectations are essential.

Preparing our students for the jobs and challenges they will face post graduation continually grows as a challenge faced by those in the education field. As this difficulty elevates, the vitality of high-quality teaching and the complexity of what it means to truly enact it. These obligations and challenges place teachers under an enormous amount of pressure, and teachers are faced with needing to decide where and how to move forward in making changes toward improvement.

Just as teachers within a school need a common, unified, and focused goal in a school’s vision for teaching and learning, they also need a specific and common framework of criteria on which to focus their efforts of improving instructional practice. This can be accomplished through a school’s adoption of a common framework of instruction.

An instructional framework can be described as a collectively shared understanding of instructional responsibilities and what it looks like to implement those in the classroom. Frameworks provide a systematic approach to unifying teachers and administration under one set of criteria that have been identified as responsibilities critical to the teaching profession. These systems typically aim also to provide feedback to educators across multiple domains and multiple criteria components within each domain by outlining specific expectations and definitions of measurement toward mastering those expectations.

Under a common framework, teachers know exactly what is expected of them, and administrators have an organized system for evaluating teachers and communicating feedback as to areas of strength and areas of potential growth. The specific organization of domains and criteria addressed depends on the individual framework, or combination of frameworks, adopted by a school or district, but consistency is seen across most widely used frameworks to encompass domains of instruction, planning, environment, and professionalism (A new instructional framework for Iowa, 2019).

Establishing rhythms of nonevaluative feedback leads to partnership, growth, and unified practice.

In the last decade, instructional coaching has sparked interest in schools for many reason including an increasing recognition that “teacher quality is a critical factor in student success” (Knight, 2012, p. 94). Instructional coaching offers a strong alternative to traditional professional development models and thus has increasing advocation in the field. Not only has a partnership instructional coaching model been found to increase implementation in comparison to traditional professional development methods, it has also shown to be more effective for communicating desired content, engaging staff, and setting expectations for future implementation (Campbell & Stanley, 1963).

A unified school vision for teaching (notable practice 1) and learning and a well-defined framework for learning (notable practice 4) provide the foundation from which schools and districts can build in developing specific teaching practices. This common vision and collective goal allows for successful coaching cycles, narrowing down the emphasis with which skills and practices the building collectively agrees to be worthy of investing in learning. Coaches do not encourage random, haphazard, self-determined best practice, but instead hone in on those practices established in the school’s common framework for learning. Districts and schools should invest in providing training opportunities for instructional coaches and teacher leaders so that they can have a deep and comprehensive understanding of the teaching practices outlined in the common framework for learning.

Developing these skills across grade levels and content areas creates cohesiveness in the school and results in students experiencing skills of the common framework and best practice throughout their entire experience at the school. Students know what to expect when these practices are put into place, and teachers benefit from prior student exposure.

These roles are then communicated to all staff numerous times throughout the school year.

Without defining teacher leadership roles, many districts’ teacher leadership programs are floundering. To implement truly effective instructional coaching and teacher leadership programming, teachers and staff need to know what to expect from their instructional coaches and what accountability and support they will receive from them. Similarly, coaches need to have their expectations clearly outlined to ensure they are meeting the needs of the district’s students and teachers as well as meeting the expectations of their administrators. It is critical that all stakeholders of the teacher leadership and coaching programs are on the same page.

Defining the coaching cycles as discussed in the fifth notable practice and tying those responsibilities into the school vision helps establish a foundation from which teachers and coaches can begin to work toward a common goal. Moore Johnson and Donaldson (2007) suggest that teacher leadership programs are suggestively more viable if roles have well-defined qualifications, responsibilities, and selection processes.

Below is an example from Opportunity Culture’s Defining Teacher-Leader Roles (n.d.) as to what these role definitions might look like. Be sure to address all needs within these roles and take into consideration which responsibilities and roles should be distributed to teachers in a classroom and which roles would need to be met by someone whose schedule is exclusively for those responsibilities.

The principal holds all employees accountable for participation, collaboration, and productivity, but she or he does not micromanage.

There is no doubt that principalship entails a great deal of difficulty and responsibility. Besides classroom teachers, principals are the most important members of the school team. They can’t always be in each and every classroom, but they need to be present and aware, checking in often and providing meaningful feedback. They need to be aware so that they can make informed decisions in the best interest of their schools and the students in them. The reality is, however, this ideal is becoming intensively more difficult to enact under the increasing responsibilities falling at the feet of today’s principals. Between addressing staff concerns, the paperwork that is now required for state and federal documentation, making both short-term and long-term decisions, hearing requests, handling complaints, and engaging with students who demonstrate behaviors, the ever-growing and surmounting responsibilities and situations that demand the attention of principals can easily become unmanageable.

Principals are no longer able to take on the weight of responsibility by themselves. In all realms of business and life, it has become critical for leaders to develop a skill for encouraging leadership across the organization. Micromanagement is not effective, and schools are no exception to this reality (Five Key Responsibilities, n.d.). Delegation and developing shared leadership are now skills that are entirely necessary for the success of a principal and his or her school.

PLCs should focus on four questions: What do we expect our students to learn? How will we know they are learning? How will we respond when they don't learn? How will we respond if they already know it?

The foundation for Professional Learning Communities is again tied back to the school’s shared vision for teaching and learning. If it is desired school to be moving toward the vision, how will it get there? The impact Professional Learning Communities can contribute to a school’s development is incredible, but to do so the structure of a PLC must be organized and structured with all organization members clearly understanding the expectations and purpose for each PLC meeting. Joe Carter, a principal in Emmetsburg, Iowa, outlines three Big Ideas for PLC meetings that are nonnegotiable as the focus for every single PLC meeting in his building. These three Big Ideas that drive PLC work are: “Focus on Learning,” “A Collaborative Culture,” and “A Focus on Results” (Carter, 2018). By emphasizing these three Big Ideas for his team’s PLC work, Principal Carter has set the framework for expectations that should guide and drive every PLC meeting. In addition to the Big Ideas identified by Principal Carter, there are several other elements of a PLC that are non-negotiable:

- Centered upon the 4 Corollary Questions: What is it we want our students to learn? How will we know if each student las learned it? How will we respond when some students don’t learn it? & How can we extend and enrich the learning for students who have demonstrated proficiency? These four questions are the backbones of PLC work. Investigating and experimenting to find answers to these questions are the reason PLCs exist. Each and every PLC meeting must address and focus on these four questions in regards to different skills that students are expected to learn.

- Norms: Norms are the rules and expectations for PLCs as developed by each individual team. Norms help teachers stay on track and allow one another to hold each other accountable for the ideals they’ve established for their work together.

- Agenda: Each meeting should follow a consistent agenda, which can be established by the team or the building leadership.

When teachers believe that it is within their power to improve student learning, they will expect great things of themselves, and student achievement will rise

The previous eight notable practices play together to increase student achievement by creating intentional, consistent, and purpose-driven schools full of growing and improving teachers through administrative direction and support. Research by John Hattie, however, would suggest that none of these factors in and of themselves will have the greatest impact on student learning. Instead, that power lies solely in collective efficacy, the belief shared collectively by teachers that they “can positively influence student learning over and above other factors” to “make an educational difference in the lives of students” (Donohoo & Katsz, 2017, p. 21).

Collective efficacy describes the shared belief of teachers and other educators that they, as a unit, can “organize and execute the courses of action required to have a positive effect on students” (Goddard, Hoy, & Hoy, 2004, p. 4) to a greater extent than students can be influenced by other, outside factors including home life and community experiences. In making efforts toward increasing student achievement and working to achieve the school’s shared vision for teaching and learning, fostering such a powerful tool as collective efficacy is a dire investment for principals, administrators, and other school leaders. If teachers and administrators desire to make an impact, they first must believe that they, as an educational unit, have the power to do just that.

Teachers’ impressions of their ability to impact student learning are greatly impacted by the connections they have made to previous experiences in regard to the efforts they’ve made and student achievement. By intentionally affording professional learning opportunities that allow and encourage teachers to make these connections between their collective actions and resulting student achievement helps develop the belief that the prior is causal to the latter. By bringing to attention these times of exemplifying efficacy, teachers are able to see evidence of these efforts having a meaningful impact on student success. Practicing making collaborative efforts to impact student learning and engaging in professional learning opportunities that teach these skills can serve as a starting point in beginning to make these connections.

Does this list match the notable practices you have observed in effective school leadership? I invite you to challenge and add to my observations. What areas do you see as crucial in the K-12 school framework? How can educational leaders provide the necessary vision for K-12 schools to follow?

Download the Notable Practices white paper

By Megan Alexander, Instructional Coach and Principal Endorsement Program student

About the Author

Gary Richardson is currently the director of Northwestern College's Master of Education program and an instructor in the Master of Education in Educational Administration program. He has worked in education for over 37 years as a teacher, principal and superintendent. He is also a school leadership coach for the Administrative Support Program through School Administrators of Iowa. He is passionate about training teachers leaders and administrators. Learn more about the Principal Endorsement program.